When I walked into the city room of the Chicago Tribune my first day on the job, I saw a sea of white male faces above white rumpled shirts; in true Front Page tradition, a few reporters puffed on cigars and a few editors wore green eyeshades. That was in 1968. When I left four years later, things hadn’t changed much, and I filed a sex discrimination complaint against the paper. Now, twelve years later, 29 percent of the Tribune’s general assignment reporters are women. The associate editor is a woman and so is the head of the sports copydesk. “In the old days, women turned on each other; now we tum to each other,” says Carol Kleiman, associate financial editor and columnist for the paper, and a member of its women’s network. “The only place I’m weak is getting women into the higher positions—running the foreign, national, and local desks. But they’ll get there,” says James Squires, the Tribune’s editor.

Gone are the days when women in journalism who wanted to write hard news were condemned to the “soft-news ghettos” of the society, food, or gardening pages, the sections considered second-class journalism by the men who run the papers. Now they not only report on issues of significance to women—from day care to birth control—but also cover the White House and the locker room, the streets of Beirut and the villages of El Salvador. Thirty-six years ago, when Pauline Frederick was hired by ABC as the first woman network news correspondent, she was assigned not only to interview the wives of presidential contenders at a national political convention, but also to apply their on camera makeup. Today, on most large papers, 30 to 40 percent of the hard-news reporters are women. In television, 97 percent of all local newsrooms had, by 1982, at least one woman on their staffs, as compared to 57 percent in 1972.

Some women have even worked their way into upper management: Mary Anne Dolan is editor of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner; Kay Fanning is managing editor of The Christian Science Monitor; Sue Ann Wood is managing editor of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat; Gloria B. Anderson was managing editor of The Miami News until October 1981, when she co-founded the weekly she co-publishes and edits, Miami Today. “I remember when there was no such thing as a woman copy editor—the reasoning being that you can’t give a woman authority over a man,” says Eileen Shanahan, former New York Times reporter (one of seven who sued that paper for sex bias) and now senior assistant managing editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the number three spot on the paper.

One hundred and twenty newspapers now have women managing editors, according to Dorothy Jurney of Wayne, Pennsylvania, an independent researcher and veteran editor whose annual survey of women in newsroom management appeared in the January issue of the Bulletin of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. And about fifty of the country’s 1,700 daily papers have women publishers, says Jean Gaddy Wilson, an assistant professor of mass communications at Missouri Valley College who, aided by grants from Gannett, Knight, and other foundations, will release in early summer the first results of what promises to be the most comprehensive study to date of women working in the news media.

The limits of change

But serious barriers do remain. “I’ve seen a lot of change, but it hasn’t gone far enough,” says Shanahan. Top management jobs in large media corporations are nearly as closed to women now as they were twenty years ago. The situation at The Washington Post is fairly typical. The Post has beefed up the number of women on its news staff considerably since it reached an out-of-court settlement in 1980 with more than one hundred women there who had filed a complaint of sex discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission; it has even appointed a woman, Karen DeYoung, as editor of foreign news, and another, Margot Hornblower, as chief of its coveted New York bureau. “The number of qualified bright female candidates has never been higher,” says executive editor Benjamin C. Bradlee. But there are currently no women staff foreign correspondents, and “there aren’t many of us in power jobs,” says Claudia Levy, editor of the Post’s Maryland Weekly section and head of the women’s caucus that negotiated the settlement. While Bradlee says he “sure as hell” plans to move women into top editing jobs, they don’t include his. “I’ve seen ten thousand stories on my possible successor, and none has mentioned a woman,” he says.

More than half of the women managing editors are at newspapers of less than 25,000 circulation; at large papers, men still hold 90.4 percent of the managing editorships, Jurney has found. Indeed, only 10.6 percent of all jobs at or above the level of assistant managing editor at all daily and Sunday papers are filled by women. And most of those editing jobs are in feature departments, positions generally not considered “on line” for top management slots, which are usually filled from within the newsroom.

In broadcasting, progress is equally mixed. Ten years ago, there were almost no female news directors. Now, women are in charge of 8 percent of television newsrooms and 18 percent of radio newsrooms. More than one-third of all news anchors are women, but there has never been a solo woman anchor—nor, for that matter, a female co anchor team—assigned permanently to any prime-time weeknight network news program. Nor is there likely to be in the near future.

On local stations, the news team is usually led by a man with a younger woman in a deferential role. Only 3 percent have survived on-camera past the age of forty; nearly half of all male anchors, on the other hand, are over forty. And only three women over age fifty appear regularly in any capacity before network cameras—Marlene Sanders, Barbara Walters, and Betty Furness. (One reason Christine Craft was pulled from her anchor slot at KMBC-TV in Kansas City, Missouri, was because she was “not deferential to men.” She was also told that, at age thirty-eight, she was “too old” for the job.)

In top broadcast management jobs, many women feel they are moving backwards. A few years ago, NBC had one female vice-president in the news division: now it has none. CBS had four out of eleven; now it has one out of fourteen. “There are no women being coached for key positions,” says a female former vice-president of the CBS news division, who requested anonymity. “There’s no more pressure from Washington, so anything management does for women it views as make-nice, as charity.”

“Women feel fairly stuck,” concurs CBS correspondent Marlene Sanders, who has broken a number of broadcast barriers—as the first woman TV correspondent in Vietnam, the first woman to anchor a network evening news show (she substituted temporarily for a man), and the first woman vice president of news at any network. “We may have to wait for another generation—and hope those men in power have daughters whom they are educating, and whom they can learn from.”

Resistance—and revenge

What progress has been made has not come easily. Although Carole Ashkinaze, for example, wanted to be a political reporter, she accepted a position as a feature columnist with The Atlanta Constitution in 1976, bringing with her nearly a decade of experience as a hard-news reporter at Newsday, The Denver Post, and Newsweek (where about fifty women filed a sex-bias complaint in 1972). Her first column—about Jimmy Carter’s 51.3 Percent Committee, formed to develop a pool of women for possible political appointment—sent ripples of disapproval through the Constitution’s management ranks. “The editors’ reaction was: ‘We hope you’re not going to do that kind of story as a steady diet,’ ” she recalls. “But women came out of the woodwork, saying ‘Please keep writing about this kind of thing.’ ” Subsequent columns were about battered women, problems in collecting child-support payments, abortion. She wrote about inequality wherever she saw it, and even began a crusade to get a women’s bathroom installed near the House and Senate chambers in the state capitol. While male legislators could run to their nearby private bathroom, listen to piped-in debates, and return to their seats in less than a minute, women legislators had to go to the far end of the capitol building and line up behind tourists in the public restroom. “They finally gave the women a restroom, and the women gave me a certificate of commendation,” says Ashkinaze.

After about a year, management gave in to her request and she was moved to the city room as a political reporter, but kept her column, in which she now writes about everything from racism to feminism to the environment. In August 1982, she became the first woman ever appointed to the paper’s editorial board. “I’m very proud of it, and very humble, because I realize it’s a result not only of my talents, but of what women in the South have been fighting for for decades,” she says. “It’s wonderful for other women at the paper to see more women here in positions of authority. It’s something we’ve never had before.” Fifteen women now hold editing and management jobs at the paper. “When I came here,” Ashkinaze recalls, “these positions truly weren’t open to women. Now, even with the political backlash in Washington, there is a much larger awareness here that women are an extremely valuable resource.”

Emily Weiner, a coordinator of the women’s caucus at The New York Times, was hired by the Times as an editorial artist in the traditionally all-male map department in December 1978, shortly after the Times had settled its class action sex discrimination suit. (The Times agreed out of court to pay $233,500 and to launch a four-year hiring and promotion program for women.) “I was in the right place at the right time,” Weiner says. “There were gold stars out there for Times managers who hired women. I am damn good at what I do, but I’m sure there are other good women who wouldn’t have gotten this job if they had applied for it earlier.

“The sad part,” adds Weiner, “is that the benefits have gone mainly to us younger women, not to those who filed the suits and took the risks, who expended their emotional energy and time and got the wrath of management.” As a friend in management told Betsy Wade Boylan, a copy editor on the paper’s national news desk who was one of the plaintiffs in the Times’ discrimination suit, “The Times is not in the business of rewarding people who sue it.”

Indeed, more than one woman who has laundered her company’s dirty linen in public has found herself writing more obits, working more graveyard shifts, subjected to lateral “promotions,” and passed over in favor of women hired from outside. But the same kind of shoddy treatment has been too often dished out to women whether they sue or not.

The Butcher treatment and other games

The story of Mary Lou Butcher is a case in point. A few months after graduating from the University of Michigan in 1965 with a political science degree, Butcher was hired by the Detroit News to write wedding announcements—the only kind of position then open to women with no prior reporting experience. (Men were trained in the city room.) Determined to move into hard news, she began writing stories on her own time for the city room and, after a year and a half of “pushing and pleading,” was transferred to a suburban bureau, a move that gave her a chance to cover local government.

Three years later, after volunteering to work nights as a general assignment reporter, she finally made it into the city room. But after about six years of covering a wide range of stories—for a while, she was assigned to the Wayne County Circuit Court—she was given a weekend shift, normally reserved for new reporters. Men with less seniority had weekends off, but when Butcher—by now a veteran of eleven years—finally asked for a better shift, she instead found a note on her typewriter saying she was being transferred back to the suburbs.

Other women at the News had been similarly exiled. In 1972 there were eight women reporters in the city room. When Butcher was “demoted” to suburbia in 1976, she was the last remaining woman reporter in the newsroom on the day shift; all the others had been moved to the life-style, reader-service, or suburban sections—or had left. When the News used its city room to film a TV commercial promoting the paper, it had to recruit women from other departments to pose as reporters.

“When I saw that note, a light finally went on,” Butcher says. “I thought: ‘Wait. There’s something strange going on here.’ I had proven myself to be a good hard-news reporter. I saw no reason for being treated like this. It took a long time for it to occur to me that there was something deliberate about what was happening here, that I was the victim of a pattern.”

As has been the case with many women reporters, that pattern also appeared in her story assignments. When she volunteered to help report on Jimmy Hoffa’s disappearance, she was turned down because, she believes, it was considered “basically a man’s story.” During United Auto Workers negotiations in the mid-1970s, she—getting much the same treatment as Pauline Frederick thirty years earlier—was assigned to interview the wives of the Ford management team negotiators; the talks themselves were covered by reporters who were male. And when an education official from Washington came to Detroit to talk about how sex stereotyping in schools can lead to stereotyping in jobs, the editor assigned her to cover it because, she recalls, “he said he wanted a light story, and ‘we figure we can get away with it by sending you.’ ” She argued with him and wrote the story straight; it was buried in the paper.

Butcher and three other News women eventually sued the paper, which agreed last November in an out-of-court settlement to pay $330,000, most of which will go to about ninety of its present and former women employees. Butcher decided to leave journalism because, she says, “My advancement opportunities were almost totally blocked at the News. And after filing a lawsuit, it wasn’t realistic to think that other media in Detroit would be eager to hire me. Management doesn’t like wave-makers.” She is now account supervisor for the public relations firm of MG and Casey Inc. in Detroit. “Newspapering is my first love, but I think the sacrifice was well worth it,” she says. “Now the News is recruiting women from around the country, putting them in the newsroom, and giving them highly visible assignments. I feel really pleased; that’s what it was all about. ”

Not all women feel that their complaints against their employers harm their careers in the long run. “Sure, there may be adverse consequences to signing on to these suits. But there are adverse consequences to being a woman working in a man’s world. Some managers may punish you for it, but others believe it shows a certain amount of gumption,” says Peggy Simpson, one of seven female AP reporters who last September won a $2 million out-of-court settlement of a suit charging sex and race discrimination. (The AP, like other defendants cited in this article who have agreed to out-of-court settlements, has denied the charges of discrimination. “But when a company settles for two million dollars, it suggests they had good reason to want to avoid going to court,” says New York attorney Janice Goodman, who represented not only the AP plaintiffs but also sixteen women employees of NBC, who won their own $2 million settlement in 1977. In such settlements, the money is usually divided among the women employees who have allegedly suffered from sex discrimination.)

Still, for various reasons, all the AP plaintiffs have left the wire service for other jobs. Simpson is now economic correspondent for Hearst and Washington political columnist for The Boston Herald. Another plaintiff, Shirley Christian, who was on the AP foreign desk in 1973, went to The Miami Herald and in 1981 won a Pulitzer for her work in Central America.

It is not only the plaintiffs who may find their jobs on the line. Vocal sympathizers within a company can suffer recriminations as well. When Kenneth Freed, who at the time was the AP’s State Department correspondent, won a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard in 1977, he says he was told shortly before his departure that the wire service would not supplement his fellowship money with a portion of his AP salary—a practice it had generally followed up to then. He later learned from friends at AP “that the reason was to punish me for my union activism—especially my role in the suit pressing for women and minority rights. They felt I had betrayed them. After all, I had one of the best beats in Washington and was paid considerably over scale. When I supported the women’s suit, it just angered them even more.” Thomas F. Pendergast, vice president and director of personnel and labor relations for the AP, says Freed was a victim of circumstance rather than of deliberate ill will. He says AP president and general manager Keith Fuller decided for financial reasons to stop supplementing all fellowships after he took over in October 1976. But unfortunate coincidences did not stop there. When Freed was ready to resume his old job after his year at Harvard, he says he was told by his Washington bureau chief that “there was no longer anything for me at the State Department.” He adds, “I told them the only thing I didn’t want to do was cover foreign policy on the Hill and, after that, it was all they offered me.” Freed quickly left AP, and is now Canadian bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times.

Newspapers and broadcast stations that have agreed to fill goals for women have often failed to meet them. They blame slow employee turnover, and the general doldrums that have hit the newspaper business, for those failures. The New York Times, for instance, agreed in its consent decree to give women 25 percent of its top editorial jobs; in fact, only 16 percent had been so filled by 1983. Out of sixteen job categories in which hiring goals were set for women, the Times had met those goals in only eight categories—mainly the less prestigious ones. “We feel it has lived up to neither the spirit nor the letter of the law,” says Margaret Hayden, counsel for the Times’ women’s caucus.

And numbers can be dressed up to look better than they are. Several women at Newsday report that, since the out-of-court settlement in 1982 of a suit filed by four women employees, lateral moves by women are sometimes listed as promotions in the house newsletter. And when attorney Janice Goodman inspected the AP’s records in 1982, she found that the wire service was giving inflated experience ratings to the men it hired, so that many were starting with salaries higher than those of women with equal experience.

A few years after the Federal Communications Commission started monitoring broadcast stations for their employment practices, the United States Commission on Civil Rights noted in its report, Window Dressing on the Set, that the proportion of women listed by stations in the top four FCC categories had risen “a remarkable—and unbelievable” 96.4 percent. In fact, the commission found that, as a result of a shuffling of job descriptions, three-fourths of all broadcast employees at forty major television stations could be classified as “upper level” by 1977, an “artificially inflated job status” that the commission found again in a follow-up report it issued in 1979.

Setting the pace—and pushing hard

Yet even after discounting for such creative manipulation of statistics, the figures do show solid gains for women. At Gannett, the largest newspaper chain in the country, chairman and president Allen H. Neuharth has been a pacesetter at moving women into jobs: its eighty-five dailies now have twelve women publishers, two women executive editors, five women editors, and fourteen women managing editors. Cathleen Black is president of USA Today and a member of the Gannett management committee. “For twenty years Neuharth has been working creatively to make it happen,” says Christy Bulkeley, editor and publisher of Gannett’s Commercial-News in Danville, Illinois, and, as vice-president of Gannett Central, in charge of overseeing six of the chain’s papers in four states. Neuharth, for instance, sent Bulkeley and another woman to the 1972 Democratic convention, which they saw as an opportunity to “produce enough copy so the all-male staff of the Washington bureau couldn’t say we weren’t doing our share of the load,” Bulkeley recalls. Shortly after, the first woman appeared as a full-time reporter in Gannett’s Washington bureau.

The AP is now hiring women at a rate equal to men for its domestic news staff. In 1973, when the suit began, only 8 percent of its news staff was female; now it is up to 26 percent, and rising. In 1973, the AP had only two or three women on the foreign desk, a position that prepares reporters for assignments abroad; now six out of seventeen on the foreign desk are women.

At Newsday, 41 percent of reporters and writers hired for the newsroom over the past nine years have been women. “Before we filed our suit [in 1975] there were no women in the bureaus, no women on the masthead, no women in positions of importance in the composing room,” says Sylvia Carter, a Newsday writer who was a plaintiff in the suit. “Now, a woman is Albany bureau chief, a woman is White House correspondent; there are lots of women editors, three women on the masthead, and a woman foreman in the composing room.”

The most visible gains have been made in cities where women have pushed hardest for them. Take Pittsburgh, for instance. In general, the town “is far and away less than progressive towards women; if someone calls me ‘sweetheart’ I don’t even notice anymore,” says the Post-Gazette’s Shanahan. But a chapter of the National Organization for Women threatened for several years to challenge local broadcast licenses in FCC proceedings if the city’s stations did not improve women’s programming and employment. The result: media women are doing very well in Pittsburgh. Today, five women hold top administrative positions at CBS affiliate KDKA-TV, including those of vice-president and general manager. At WTAE-TV, Hearst’s flagship station, four women hold top-level jobs. KDKA radio has three women in high executive news jobs, and three women co anchors. And Madelyn Ross is managing editor of Shanahan’s rival paper, the Pittsburgh Press.

“When one of the media is a target, it raises other people’s consciousness,” says ex–Detroit News reporter Butcher. “It has a ripple effect.” At the Detroit Free Press, for example, the managing editor, city editor, business editor, graphics editor, and life-style editor are all female. (At Butcher’s former paper the news editor is a woman and women hold about 30 percent of the editorial jobs.) In addition to Butcher’s suit against the News, the Detroit chapter of NOW and the Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ also negotiated aggressively for women’s and minority rights with local broadcasting stations. Today, two major network affiliates—WDIV-TV and WXYZ-TV—have women general managers.

Pressure on broadcasting stations in the form of FCC license challenges has subsided in recent years, in part because improvements have been made in the broadcast industry, and in part because “we don’t have the votes anymore at the FCC, which is now controlled by right-wing Republicans,” says Kathy Bonk, director of the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund Media Project in Washington, D.C. But in many broadcast news organizations a solid groundwork has been laid. “Those women created opportunities for the rest of us, and I will always be grateful for that,” says Sharon Sopher, who was hired as a news writer and field producer for NBC in 1973, a few months after several NBC women employees filed a sex-discrimination complaint with the New York City Commission on Human Rights. Sopher became the first network producer to go into the field with an all-woman crew, and has been allowed to do stories previously off-limits to women—from a feature segment on street gangs to a special assignment to cover the Rhodesian war from the guerrilla perspective. Her first independent documentary, Blood and Sand: War in the Sahara, aired on WNET in 1982.

Will the advance be halted?

Once at or near the top, women can have significant professional impact on the attitudes of their male colleagues. Richard Salant was president of CBS News in 1975 when Kay Wight was appointed director of administration and assistant to the president. “She made me realize what a rotten job we were doing about hiring and promoting women,” Salant says. “She kept at me all the time, in a diplomatic but insistent way, about how few women we had in every department except steno and research.” As a result, Salant, who has four granddaughters, began to insist on monthly reports from his subordinates on the numbers of women in each department. “I finally wouldn’t approve any openings unless they put in writing what they had done to recruit women and minorities. The paperwork was a pain—but at least it made people conscious of the issues.” During his time at the helm (he left CBS in 1979 and is now president and chief executive officer of the National News Council) the number of women in important positions rose dramatically, but not enough to satisfy Salant, who maintains that his greatest disappointment is that “I never got a woman on 60 Minutes.” (Salant was among the first members to resign from New York’s all-male Century Club over its discriminatory policies. Similarly, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, chairman of the board of The New York Times, warned his top executives last year that, as of January, they would no longer be reimbursed for expenses incurred at the club.)

When Chicago Tribune editor Squires was Washington bureau chief for the paper, Eileen Shanahan, then with The New York Times, and Marlene Cimmons of the Los Angeles Times convinced him to join them in a project to eliminate sexism from the AP and UPI stylebooks. They “raised my sensitivity about women’s issues above what I ever thought it could be raised,” he says. Now, many women at the Tribune feel they have an ally in Squires. “The pioneer women in journalism were friends of mine—Nancy Dickerson, Eleanor Randolph, Elizabeth Drew,” he says. “A lot of them had a rough time just because they were women. And seeing what has happened to them makes me feel I have to take steps to overcome the problems of the past.” But performance can lag far behind promise. Five major editing jobs opened last year at the Tribune—managing editor, copydesk chief, metro editor, assistant metro editor, and national editor—and none of them went to a woman.

“The battle isn’t over for equal rights in any profession, including journalism,” says Helen Thomas, UPI’s veteran White House reporter, who has covered six presidents and toted up a number of firsts—first woman president of the White House Correspondents Association, first woman officer of the National Press Club, first woman member of the Gridiron Club. Yet she remains optimistic. “It is impossible for women to lose what we’ve gained,” she says. “We’re now secure in our role as journalists—we just have to expand that role.”

“We’re fighting against enormous odds,” says Joan Cooke, metro reporter for The New York Times, chair of the Times unit of The Newspaper Guild of New York, and a plaintiff in the suit against the Times. “Look at the masthead. [Out of seventeen people listed, two are women.] That’s where the power is, and they’re not going to give up power easily. And most women don’t want to devote all their extra energy to equal rights—they want to go home like everybody else, to be with their families or friends. But if the spirit is there, and the will is there, it can be done.” Sylvia Carter, a Newsday writer who was a plaintiff in the sex discrimination case against her paper, advises women to “be tough, keep your sense of humor, and form a women’s caucus—but don’t do it on company time.”

Slowly, discrimination is easing as men see that women can do the job. The courage, persistence, and sheer hard work of women journalists have made these changes possible. But, at too many news organizations, women have yet to scale the topmost peaks; despite their increasing visibility, they do not have much more power than before. And the important question is: Will they ever? In the past, government pressure in the form of lawsuits and the threat of revoking broadcast licenses forced the news media to give women a chance. Now, in the hands of a conservative administration, the tools by which that pressure is exerted—the EEOC and the FCC—are being allowed to rust. It is up to the news media, then, to spur themselves on toward greater equality in the newsroom and resist the temptation to backslide into the patterns of discrimination that have limited and punished women because of their sex.

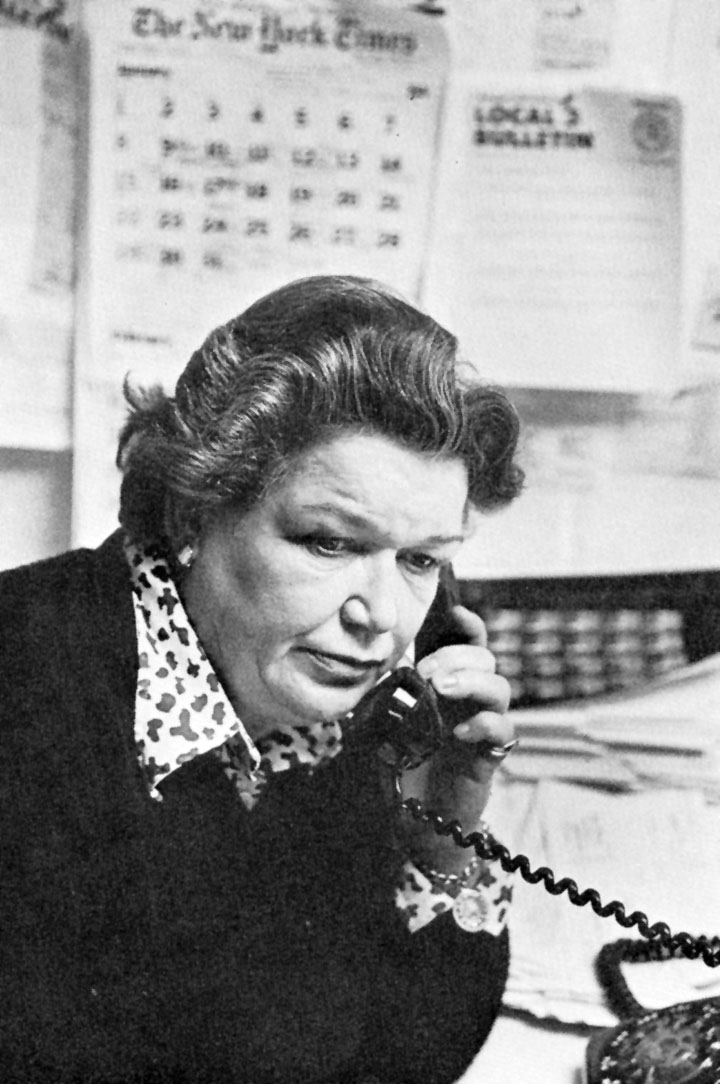

TOP IMAGE: Joan Cooke in 1984; Photo by Harvey Wang, courtesy of photographer